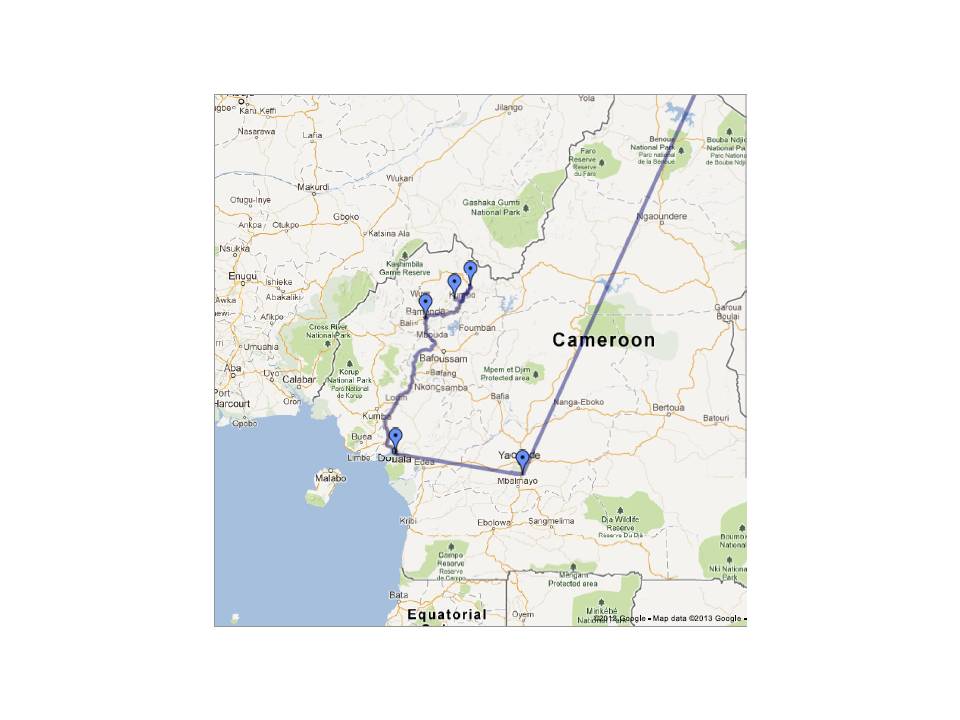

One of the (many) challenges to starting a new project is visiting a country that often none of the team members have been to before. Many of the small villages EWB tends to work with are, quite literally, not even on the map, so teams do not have the luxury of Googling for places to eat and sleep. Having reliable in-country contacts is important for planning the first assessment trip, but once you’re on the ground, it’s your responsibility to gather as much mapping information as possible to lay the framework for future trips.

Existing maps may be inadequate

Below is a series of maps of Bamenda, the capital city of the North West Region, from three popular map services. Even in this city of approximately 800,000, the map information is limited and varies quite a bit depending on the source:

- Bamenda (OpenStreetMap)

- Bamenda (Google Maps)

- Bamenda (Apple Maps)

As you can see above, Google Maps has the greatest level of detail, Apple Maps the least, and OpenStreetMap somewhere in the middle. Moving on to Ndu, a smaller town of about 20,000 people, and the closest town to Mbokop, the information gets even more sparse:

- Ndu (Google Maps)

Again, Google Maps provides the most detail (although still not much). Apple Maps knows where Ndu is, but not much else, and OpenStreetMap doesn’t even mark the location of the town at all. Of course Mbopkop itself isn’t identified on any map, so one of the goals of this first assessment trip is to gather as much cartographic information as possible.

Make your own map

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) is a broad field, but can be boiled down to the basic concept of associating a piece of information with a geographic location, often GPS coordinates. The piece of information can be anything from the name of a hotel, to a photo, to detailed demographics about the inhabitants of a house. This information can then be visualized on a map to examine population densities, proximity of water sources, or simply plan where to buy supplies.

The GIS data that we collect on this first trip can be roughly divided into two categories: project data and travel data. Project data is information pertaining to water infrastructure and public health. This might include locations of standpipes, spring boxes, rivers, streams, lakes, and latrines. Locations of schools, religious buildings, meeting spaces, and markets for purchasing construction supplies would also fall into this category.

Travel data consists of information useful for travel logistics. Places such as hotels, airports, banks/money exchangers, and shops for food/bottled water would fall under this category. If time permits, it is also useful to map the streets of a town or village to use on future trips.

Collecting data

Collecting GIS data is just a matter of having a hand-held GPS device. A basic hand-held model can be had for around $100, but you can easily spend $500+ for additional features such as a 3-axis electronic compass and barometric altimeter. That said, even the most basic models have all the capabilities required for basic GIS data collection.

Collecting GIS data is just a matter of having a hand-held GPS device. A basic hand-held model can be had for around $100, but you can easily spend $500+ for additional features such as a 3-axis electronic compass and barometric altimeter. That said, even the most basic models have all the capabilities required for basic GIS data collection.

The Garmin eTrex 20 is one of the GPS devices we’ll be taking on our first assessment trip and is on the lower end of the price range. Two important features that make data collection easier are the ability to mark way-points and record tracks. A way-point is a point of interest that is saved in the GPS device’s memory. This might be the location of a standpipe or building of interest that you want to save and come back to later. Recording a track is a useful feature for mapping the streets of a town or village. When recording a track the GPS device essentially saves a breadcrumb trail of where you are walking. Using this feature you can walk around a town exploring all the streets and create a street map. Another useful feature of recording a track is that if you get lost, you can use the recorded track to backtrack.

After you get home

Since EWB teams typically work in remote locations with limited access to power and internet, much of the data processing will happen back home. Most GPS devices have the capability to download saved way-points and tracks to a computer. This data can then be imported into Google Earth and shared with team members as a quick visualization of the way-points you’ve marked and tracks you’ve walked.

If you’re more ambitious, you can choose to submit your data to the OpenStreetMap (OSM) project and share what you’ve collected with the world. OSM can be thought of as a Wikipedia for maps. People from all over the world submit cartographic data they’ve collected to create a more accurate map of the world. A great beginners’ guide is available that covers everything from collecting data to submitting to OSM.

Submitting your data to OSM has the added benefit of helping people other than just your EWB team. Everyone from local residents, to tourists, to other aid groups will be able to see the streets you’ve mapped, the shops you’ve identified, and the hotels you’ve marked. Submitting your data will ensure that it’s available to anyone who needs it for years to come, even as project team members come and go.